VIEWING ROOM — LOURDES GROBET

Lourdes Grobet (Mexico City, 1940) is one of the most renowned contemporary photographers on the current art scene. Her work on Mexican wrestling has earned her wide international recognition, consolidating her view of the country’s urban culture. RocioSantaCruz brings together a careful selection of her work in the exhibition Lourdes Grobet. Lucha libre, which can be visited at the ArtsLibris bookshop, located inside the gallery, from the 5th of February. On the occasion of the publication of her photobook, Lucha libre. Retratos de familia, published by RM and available at ArtsLibris, RocioSantaCruz is preparing an extensive programme of activities and dialogues on the photographer’s work in the gallery’s courtyard.

“I returned to Mexico, burned everything I had painted and drawn”

Lourdes Grobet uses photography to undo the seams of power and censorship. Her art resorts to interdisciplinary, or rather, antidisciplinary practices: film, installation and performance come together in the visual experimentation of this photographer, whose gaze is always directed towards the blind spots of representation. Her work is a constant search for new artistic languages, as well as a defiance of any kind of formal or conceptual authority. It is not technique that sets the pace, but the affirmation of freedom.

Grobet studied Fine Arts at the Universidad Iberoamericana in Mexico. Her interest in visual expression became clear to her as a child, when hepatitis forced her to stay in bed. Illness and rest offered her a space to redefine her relationship with her environment and with herself. She began to draw. Through her eyes, she says, she was able to understand the world in a clearer, more intense way. An education in painting was, then, a logical step. However, her time at the academy meant a break with what was established, with the canons and schemes that dictated artistic production. A break with painting too. There she met Mathias Goeritz and Gilberto Aceves Navarro, who brought her closer to multimedia practices. She travelled to Paris in the late sixties, soaking up the revolutionary spirit that filled the streets and cultural movements. When she returned to Mexico, she gave up painting and took up photography as her main language.

Grobet’s photography developed in a context of effervescence and creativity. The 1970s in Mexico witnessed a period of rebellion against the conservatism of traditional artistic proposals. Experimental photography clubs emerged, rooted in the collective search for new expressive horizons. These spaces marked Grobet’s career. For her, the image is not a final goal, but a support that allows the author to flesh out an idea, to capture it, to share it, to open it up to a dialogue between her gaze and the spectator. Photography offers her the possibility of opening up her art to the public, of democratising it. As Walter Benjamin pointed out, the infinite reproducibility of the photographic image breaks with the hierarchies associated with the idea of an original. Photography is not measured by the acquisition of the “object” – since countless copies can be made from the same negative – but by the capacity to transgress its own context of production, to reach unforeseen audiences.

“Ours is a culture of masks”

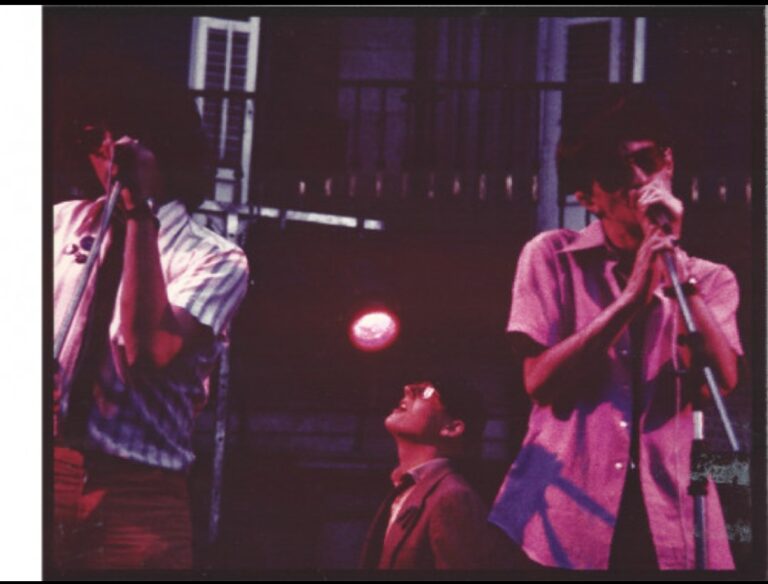

Grobet displays an intuitive, as well as coherent, gaze. Hers is not a coherence born of convention, but born of the desire to show what remains hidden, set apart, relegated to the margins of society. Her work on wrestling explores the cultural roots of urban Mexico. For decades, she has portrayed the most emblematic characters in and out of the ring. Grobet’s portraits stem from a childhood prohibition. Her father, a wrestling fan, refused to take her to the fights because she was a woman. Her reaction, years later, was to make enter the scene armed with a camera, and to make a place for herself. From this symbolic transgression, a strange and tender archive was gradually woven. A repository of lives, rituals and masks.

The camera, according to Grobet, has always an aggressive element. A form of violence. That is why her practice as an artist is oriented towards relationships rather than results. “If I don’t establish a relationship with the people I’m going to photograph, I can’t take the camera out,” she says. It is revealing that, in a setting as apparently brutal as wrestling, the photographer highlights the violence of the gaze. One of the strong points of her work is, precisely, her ability to look into the power relations that cross the field of representation. Wrestling, she says, is not a violent sport. “There is violence, but it is all about a very fundamental thing: the meeting of two bodies”. Grobet delves into this delicate balance between the fundamental and the artificial, body and mask, impact and choreography. The result is eloquent: the photographer manages to displace violence, to go beyond its exaggerated display, and to compose a richer, more complex visual landscape. While the violence of wrestling is more parodic than cruel, Grobet urges us to question the violence we don’t see, the violence that hurts without making a sound.